Short Biography

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko, the great Ukrainian poet, writer, artist, and public and political figure, was born on March 9, 1814, in the village of Moryntsi, Kyiv gubernia, in the Russian Empire (today Ukraine). His parents, Kateryna and Hryhoriy, were serfs on the land of Vasiliy Engelhardt.

His grandfather, who had witnessed peasant uprisings, had a significant influence on the young boy. Taras's literate father, sent his son to apprentice with, and be educated by, a deacon. In 1823, his mother died, followed by his father in 1825. For some time, little Taras served as a houseboy and was already showing a talent for drawing. At fourteen, he became a domestic servant to Pavlo Engelhardt who had inherited the estate from his father, Vasiliy.

In the spring of 1829, Taras travelled with Pavlo Engelhardt to Vilnius, Lithuania. When the Polish rebellion for national liberation from Russia began in November 1830, Engelhardt left for the Russian capital, St. Petersburg. Shevchenko remained with his landlord's servants in Vilnius and was witness to the revolutionary events. At the beginning of 1831, he left for St. Petersburg and in 1832, Engelhardt "contracted" him to the master painter Vasiliy Shiryayev, with whom the lad experienced a hard school of professional training.

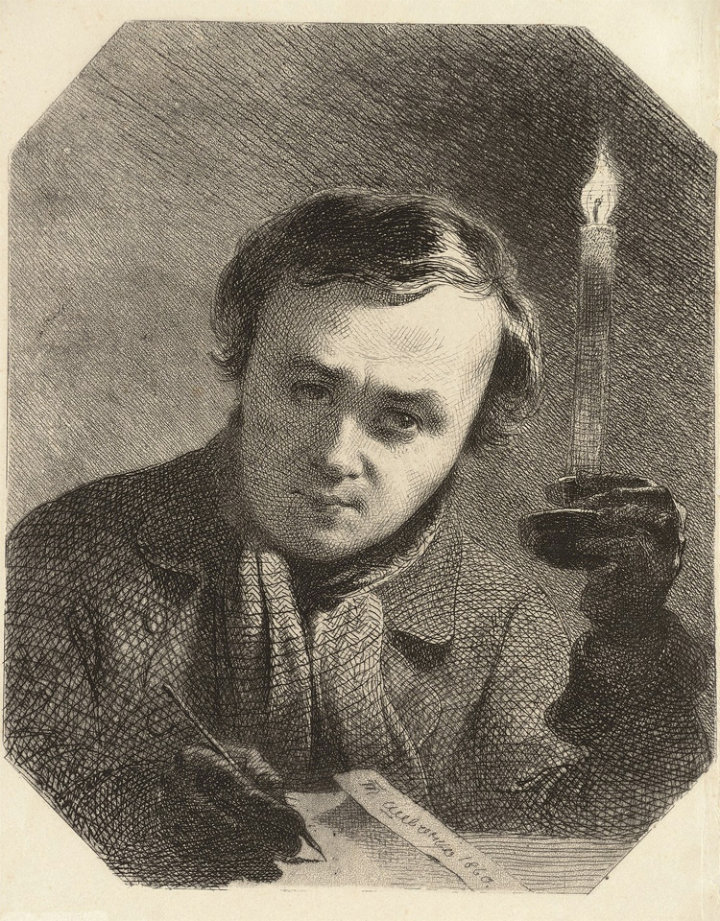

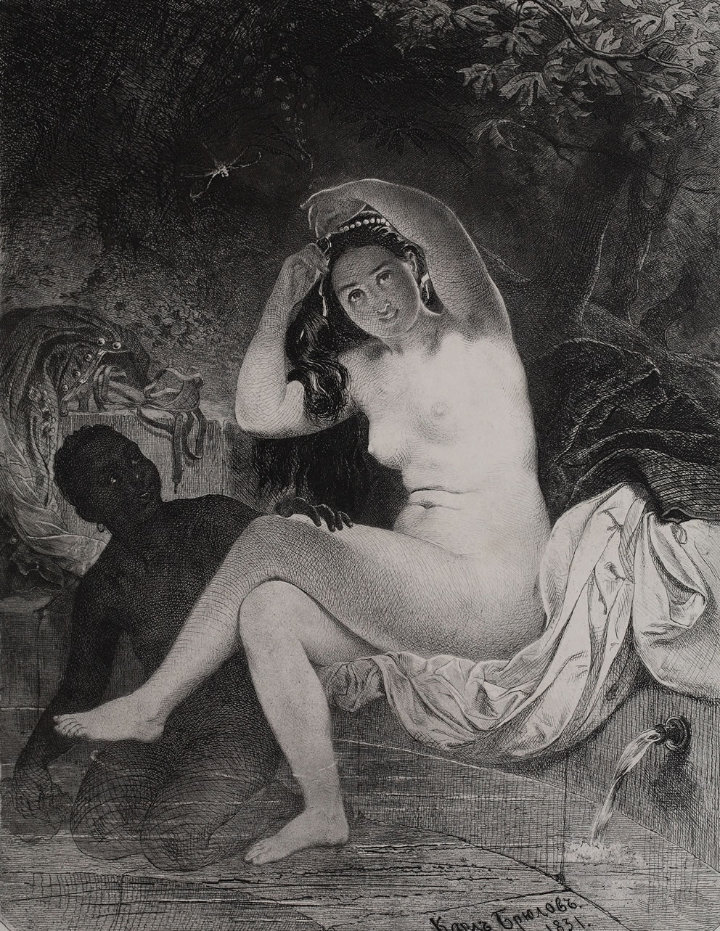

Recognizing his talent as an artist, prominent members of the intelligentsia, who had befriended Shevchenko, arranged to buy him out of serfdom. The 2500 rubles required were raised through a lottery in which the prize was a portrait of the poet Vasiliy Zhukovsky, painted by Karl Bryullov. The release from serfdom was signed on April 22, 1838. That same year, approval of Shevchenko’s drawings by the Association for the Encouragement of Artists, guaranteed his acceptance into the Imperial Academy of Arts as an external student, practicing in the workshop of Karl Bryullov.

In January 1839, Shevchenko was accepted as a resident student at the Association for the Encouragement of Artists. At the annual examinations at the Imperial Academy of Arts, he was awarded the Silver Medal for a landscape painting and in 1840, he was again given the Silver Medal, this time for his first oil painting, A Beggar Boy Giving Bread to a Dog.

In the library of Yevhen Hrebinka, he became familiar with anthologies of Ukrainian folklore and the works of I. Kotlyarevsky, H. Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, and the romantic poets, as well as many Russian, East European and world writers.

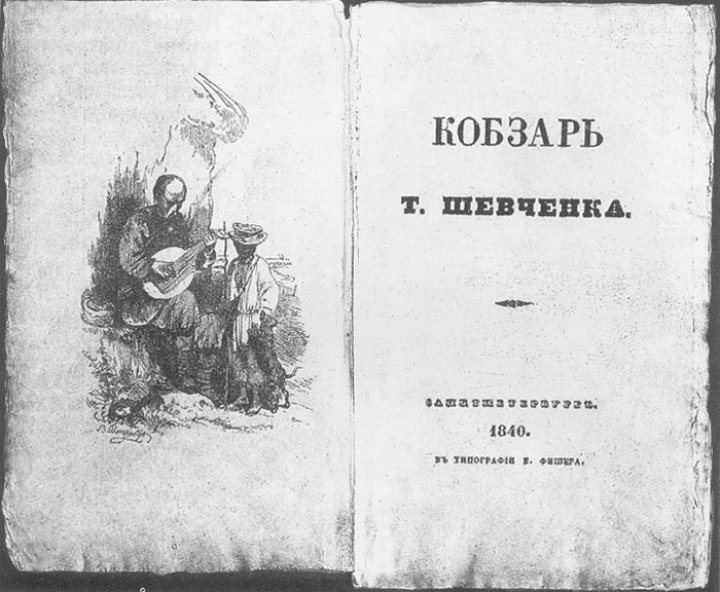

Shevchenko began to write poetry even before being freed from serfdom. In 1840, the world first saw Kobzar, his first collection of poetry. In 1841, the epic poem Haidamaky appeared as a separate volume. In September of that same year, Shevchenko received his third Silver Medal – for his watercolour painting, The Gypsy Fortune Teller. Just as significant is his oil painting Kateryna, based on his poem of the same name.

Shevchenko also wrote plays; in 1842, a fragment of the tragedy Mykyta Haidai appeared, and in 1843 he completed the drama Nazar Stodolya.

In this period, Shevchenko’s poetry displayed a deep national sense which was to remain throughout his life. “Body and soul, I am the son and brother of our unfortunate nation”, he wrote.

As his opposition to the social and national oppression of the Ukrainian people grew, tsarist censors deleted many lines of his poetry and created problems for the publication of his work. None of the critics of Kobzar, however, was able to deny the genius of Shevchenko.

In 1843, the poet left St. Petersburg, arriving in Ukraine at the end of May. In Kyiv, he produced many paintings and met with prominent members of the intelligentsia such as Mykhailo Maksymovych and Panteleimon Kulish.

That summer in Ukraine, he visited the sites of the former Zaporozhian Cossack Sich, and in September he went to Kerelivka where, after a fourteen- year separation, he reunited with his brothers and sisters. During this visit, Shevchenko made many pencil studies for a projected book of engravings to be called Picturesque Ukraine. At the end of February, he returned to St. Petersburg.

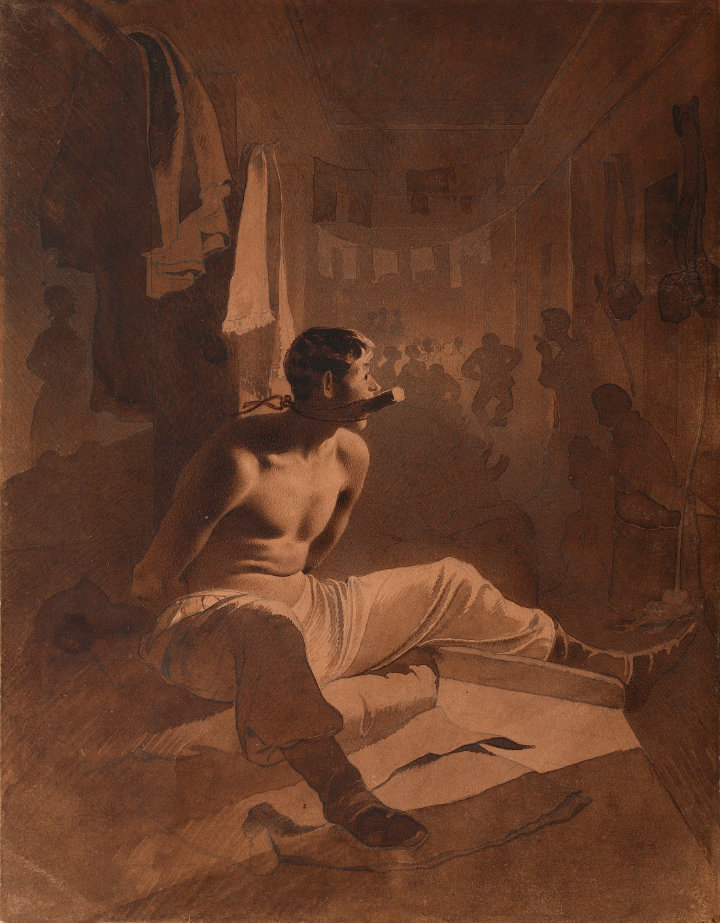

The oppression of, and inhumanity toward, the workers and peasants witnessed by him in Ukraine, gave rise to new themes in his poetry. Also influential were the works of the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz, especially in Shevchenko’s political satire.

On March 22, 1845, the Council of the Imperial Academy of Arts granted Shevchenko the title of artist and on that same day, he requested permission to travel to Ukraine.

He visited Kerelivka, and in the fall of 1845, on an appointment by the Archeographic Commission, left to paint the historical and archeological sites of Poltava. In Myrhorod, he wrote the mystery play The Great Vault, and in late October, went to Pereyaslav, where he lived until early 1846.

In the spring of 1846, Shevchenko lived for some time in Kyiv, where he met the members of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius . His radical views had a great influence on the program of this secret society.

In 1847, arrests began of the society members; Shevchenko was arrested on April 5, on a ferry crossing the Dnipro River near Kyiv. The following day, he was sent to St. Petersburg where he was imprisoned. Here he wrote the cycle of poems In the Dungeon. Of all the members of the Brotherhood who came under investigation, Shevchenko was punished most severely: he was exiled as a private with the military detachment at Orenburg. Tsar Nicholas I, in confirming the sentence, wrote, "Under the strictest surveillance, with a ban on writing and painting."

On June 8, 1847, Shevchenko was posted to Orenburg, where he served until, he was later sent to the fort at even more distant Orsk. From the very first days, he violated the tsar's order by transcribing In the Dungeon into a small secret book he kept hidden in his boot. In 1848, he was included as an artist in the Aral Sea Survey expedition. In 1850, he was arrested for violating the tsar's order. Warned by his friends, the poet was able to give them his notebooks and to destroy some letters. He was taken to Orsk for questioning, after which he was sent to a remote fort in Novopetrovsk. Once again, strict discipline was imposed, and the poet was subjected to even more rigorous surveillance. It was not until 1857 that he finally returned from exile, thanks to the efforts of friends.

While awaiting permission to return, Shevchenko began a diary which serves as an important documentation of his political views. On August 2, 1857, after receiving permission to travel to St. Petersburg, he left the fort at Novopetrovsk. However, in Nizhniy Novgorod, he learned that he was forbidden to go to Moscow or St. Petersburg, on pain of being returned to Orenburg.

In Nizhniy, the winter of 1857-58 was a very productive time for Shevchenko. He created many paintings, particularly portraits, edited and transcribed into Bilsha knyzhka (The Larger Book) his poems from the period of exile, and wrote new poetic works. After finally receiving permission to live in the capital, he left for St. Petersburg where he devoted his greatest attention to engraving, becoming a true innovator in this field.

In May, 1859, Shevchenko received permission to go to Ukraine, where he intended to buy a plot of land not far from the village of Pekariv, build a house, and settle down. In July, he was arrested on a charge of blasphemy but was released and ordered to St. Petersburg where he arrived on September 7. Nevertheless, to the end of his life, the poet dreamed of settling in Ukraine.

Despite physical weakness resulting from a decade of exile, Shevchenko's creative strength was inexhaustible, and in his last period of work he embodies the dream of the people for a free and happy life. Shevchenko understood that the peasants would gain their freedom neither through the kindness of the tsar nor through reforms, but through struggle. He created a gallery of images – Champions of Sacred Freedom – of fighters against oppression and tyranny.

On September 2, 1860, the Council of the Academy of Arts granted Shevchenko the title, Academician of Engraving.

Shevchenko began to feel increasingly ill, and complained in letters about the state of his health. He died in his St. Petersburg apartment at 5:30 a.m. on March 10, 1861. At the Academy of Arts, over his coffin, speeches were delivered in Ukrainian, Russian, and Polish.

The poet was first buried at the Smolensk Cemetery in St. Petersburg. Immediately, his friends undertook to fulfill his wish expressed in Zapovit (Testament) and bury him in Ukraine. The coffin with Shevchenko’s body was taken by train to Moscow, and then by horse-drawn wagon to Ukraine.

Shevchenko's remains entered Kyiv on the evening of May 18, 1861, and on May 20 they were transferred to the steamship Kremenchuk which took Shevchenko's remains to Kaniv where on May 22, 1861, Taras was buried on Chernecha Hill (now Taras Hill) by the Dnipro River.

A tall mound was erected over his grave, and has become a sacred site for the Ukrainian people.