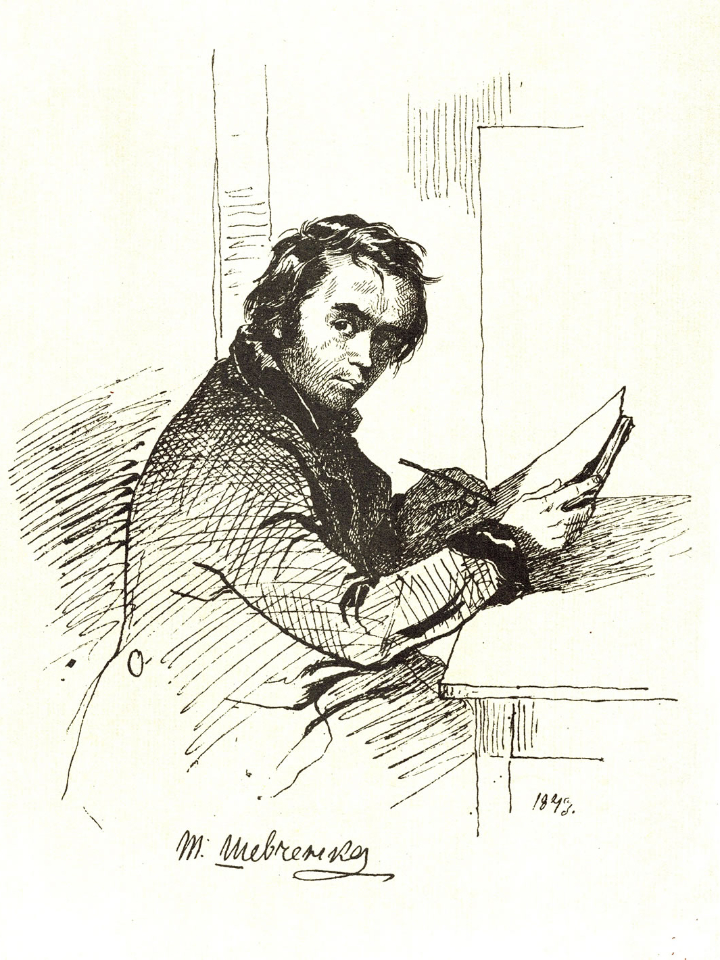

St. Petersburg Period

In February 1831, on the eve of his seventeenth birthday, Taras Shevchenko arrived in St. Petersburg from Vilnius along with the rest of Pavlo Engelhardt’s servants. It was here, in the capital and centre of cultural life of the Russian Empire, that Shevchenko was to mature, first as an artist, and as a poet, writer and activist.

His master, accepting that the youth would not make a good house servant but wanting a "court painter", apprenticed young Taras in 1832 to the stern and arbitrary Vasiliy Shiriayev. As a famous painter, decorator and art expert, he was engaged in painting the walls and ceilings of homes of the St. Petersburg elite, churches, and public buildings.

As Shiriayev was in contact with the elite of tsarist society, it is logical to assume that his young apprentice was exposed to many of the ideas circulating in the Russian capital. Popular amongst the intelligentsia were ideas of reform, many of which were informed by the ill-fated 1825 Decembrist uprising of young officers who had been strongly influenced by the philosophy of the French Revolution. In later life, a more politically mature Shevchenko would refer to the Decembrists as "the first Russian heralds of freedom". While in Vilnius, Taras had also witnessed, firsthand, the Polish uprising against tsarist rule.

While a good part of Shevchenko's apprenticeship was spent mixing paints and delivering items to various of Shiriayev's projects across St. Petersburg, he still managed to learn much from the master painter and to develop his own talents. Although he was still officially a serf, his apprenticeship nonetheless allowed him a certain degree of personal freedom. In his spare time, usually in the evenings, he would wander the city making sketches, often in the Summer Gardens during the northern "white nights".

It was there that Shevchenko met Ivan Soshenko, an artist and fellow Ukrainian, in July of 1835. Soshenko took the talented youth under his wing, teaching him the basics of painting and introducing him to some of the most enlightened and cultured members of St. Petersburg society, including the Russian artist Karl Bryullov, the poet Vasiliy Zhukovsky (who had been a tutor to the tsar's family), Ukrainian writer Ivan Hrebinka, the conference secretary of the Academy of Arts V. Gregorovich and others.

Shevchenko won the hearts of this segment of Russian society, the members of which quickly identified the young man's talents and recognised that they could only be properly developed if he were a free man.

Accordingly, the artist Karl Bryullov, whose works were much in demand, painted a portrait of Zhukovsky which was raffled off, raising the 2500 roubles necessary for Shevchenko to receive his Certificate of Freedom on April 22, 1838.

Ironically, on his arrest in 1847, Shevchenko was reproached for his "black ingratitude", as the rumour had circulated that the tsar's family had purchased all the raffle tickets and, as a result, had secured the freedom of the serf who then went on to ridicule and attack them in his poetry. While it is true that the tickets were bought for the most part by members of the court, it was merely to obtain a work of fine art for a low price.

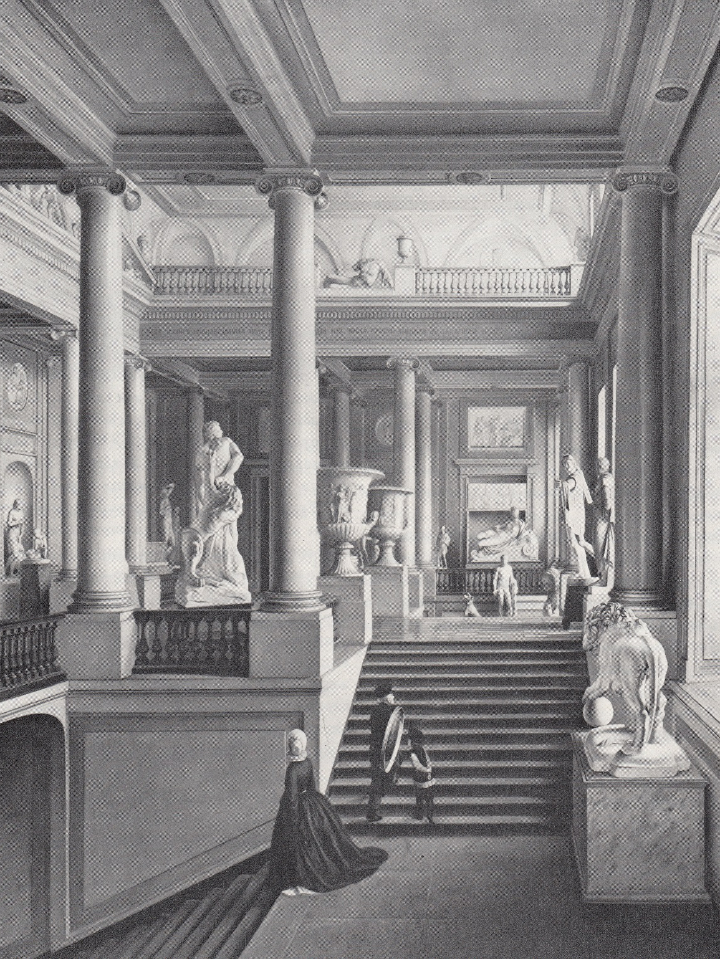

With his freedom attained, in 1838 Shevchenko became an external student at the Academy of Arts, studying under Karl Bryullov. In January of 1839, he was accepted as a resident student of the Association for the Encouragement of Artists, and at the annual examinations at the Academy was awarded a silver medal for a landscape painting. The following year, he again won a silver medal, this time for his first oil painting, The Beggar Boy Giving Bread to a Dog.

As his artistic talent developed, Shevchenko continued to move in the circles of the progressive intelligentsia and to broaden his world view. He took courses in zoology, physics and philosophy, studied the French language and avidly read literature - Homer, Goethe, Schiller, Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, Shakespeare, Defoe, Mickiewicz, Pushkin, Gogol and many others. In art, he became a critical realist and applied his approach to portraiture, etching and illustrating.

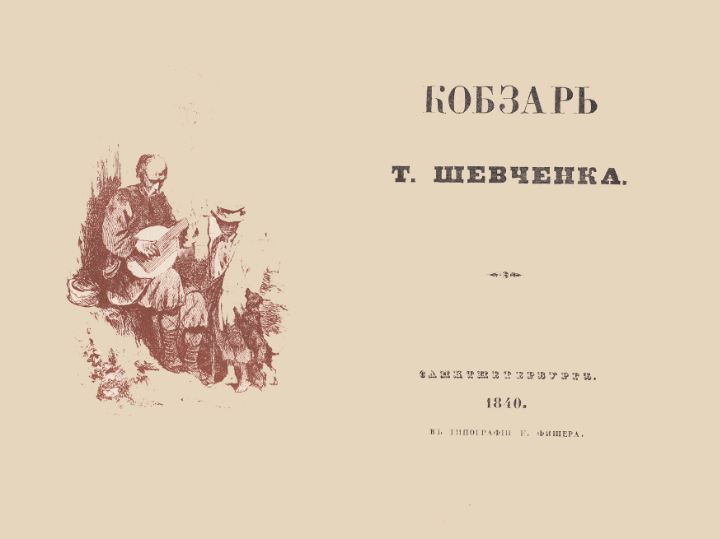

However, it is for his written work that Shevchenko is best remembered. According to his own memoirs, he first began to write verse during his visits to the Summer Gardens in 1837. He became so immersed in his writing that, by 1840, he was able to publish his first collection of poetry. It was called Kobzar and contained only eight verses, with a forward in verse form, the now famous Dumy moyi.

The Kobzar met with mixed reaction. Chauvinistic elements of society scoffed at his efforts, calling him a peasants’ poet and suggesting Shevchenko cease writing in the Ukrainian language.

The more enlightened, though, praised his poetry for its lyricism, depth, and love of his native land and people. In Ukraine, Shevchenko's poetry became an almost overnight sensation.

The appearance of the Kobzar, aside from being a turning point in Shevchenko's life, represented a milestone for Ukrainian language and culture, often denigratingly referred to as "Little Russian", giving it a legitimacy which had, to that point, been denied. The appearance of Ivan Kotliarevsky's Eneyida in the early 19th century was regarded as the true beginning of Ukrainian literature; the appearance of the Kobzar and subsequent works by Shevchenko rounded out the process.

It should be noted that Shevchenko did not write exclusively in Ukrainian. A few poems, his drama Nazar Stodoyla, and his prose were written in Russian. However, the bulk of his work was in the Ukrainian language and his themes were overwhelmingly based on Ukrainian history and traditions, the conditions of serfdom, and the fate of the common people.

For Shevchenko, the enemy was always the oppressor, regardless of ethnicity, a view reinforced by his 1843 visit to Ukraine during which he came face to face with the cruel realities of the economic, social and national oppression by the tsarist regime in the Russian Empire.

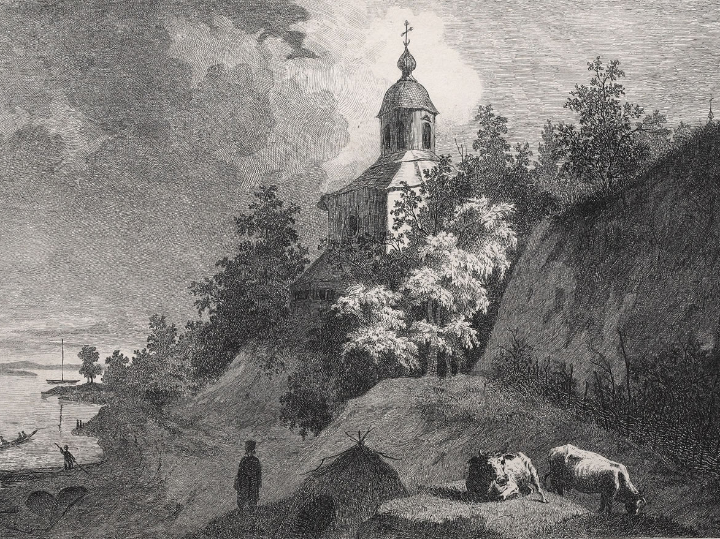

Following his visit to Ukraine, Shevchenko returned to St. Petersburg to complete his studies, to continue writing and publishing poetry, and to produce a series of etchings entitled Picturesque Ukraine. He graduated from the Academy of Arts in 1845 and almost immediately returned to Ukraine.

In Kyiv, Shevchenko contacted the secret society called the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, quickly becoming one of the leaders of its radical faction. While some members of the society saw reform as the solution to the ills of tsarist society, the radical faction saw rebellion and popular uprising as the sole means of overthrowing their masters.

During this period, Shevchenko was hired by the Archeographic Commission to travel through Kyiv, Poltava and Volyn provinces to record, in sketches and paintings, significant cultural sites.

In 1847, the members of the Brotherhood were betrayed by a police informer. Shevchenko was arrested on April 5 and transported to St. Petersburg for disposition by the tsarist authorities. The more liberal, or reformist, members received very lenient sentences for repenting. But Shevchenko refused to apologise for writing subversive and "openly unlawful" verses, some of which ridiculed the tsar's family. In his defence, he denounced tsarist repression in Ukraine and throughout the Empire.

As punishment, he was sentenced to be exiled as a rank and file soldier to Orenburg in the East. He was to be kept under strict scrutiny so that "from him wouldn't come, in any form, any outrageous or libellous works". To this order, the tsar personally added, "He is to be under the strictest surveillance, with prohibition to write and to paint".

It is interesting to note that Shevchenko's colleague in the radical wing of the society, Mykola Hulak, who also refused to repent, received a three-year jail sentence. Shevchenko's sentence, had Tsar Nicholas I not died ten years later, would have been for life.