Childhood

Taras Shevchenko, the son of serfs, was born on the estate of Baron Vasiliy Engelhardt on March 9, 1814. One of six children, he was little more than a possession of his master. He was born in the village of Moryntsi, some 200 kilometres south of Kyiv, an area which in earlier generations had been the home of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. In 1816, the Shevchenko family moved to the village of Kerelivka (now Shevchenkove), where Taras spent his childhood years. Amongst the peasantry, burdened by the brutal and unjust system of serfdom, tales of folk heroes and their struggles for freedom were commonplace, serving as relief from daily toils and providing hope for a better future. It was in such an environment that the young Taras and his siblings were raised.

Shevchenko's parents, Hryhoriy and Kateryna, worked Baron Engelhardt’s fields, as did his older brother Mykyta. As was usual in those times, the serfs laboured five days for their master, and one for themselves. His father also worked on occasion as a chumak, a teamster, hauling salt for Baron Engelhardt from southern Ukraine. It appears that his father would sometimes take Taras with him on these trips, as young children were not obliged to work for their master. During these trips, the boy was able to see some of the world, including such major centres such as Elizavetgrad and Uman.

His mother, who worked the fields during the growing season, spent the winters at home, as did most peasant women, spinning and weaving cloth for the master. Inside the household, as was typical, the older children took care of the younger ones. In the Shevchenko household, older sister Katrusya was the mainstay and had a significant influence on her younger brother. It appears he was upset when she married and moved away, and it was to her home that Taras went a few years later, after fleeing a brutal deacon for whom he worked.

The family’s home life was a happy one in terms of human relations, but a hard one in terms of material possessions and human need. Often, there was a shortage of food, particularly after the hard winter months. Shevchenko himself noted that his mother would often refuse to eat after working the fields all day, claiming she wasn't hungry. He later concluded that she didn't eat because she wanted the children to be better nourished. This is underscored by the fact that his youngest sister, Mariyka, who was forced to fast during the Lenten period after a winter of food shortages, went blind due to malnutrition.

Another influence on Taras was his paternal grandfather, Ivan, who often related stories to the young boy of the struggles of the peasantry and their not infrequent rebellions and violent uprisings. These stories likely formed the basis for much of the poet's later works, such as Haidamaky.

The greatest influence on the boy, however, was simply the hard facts of peasant life. Until the abolition of serfdom in 1861, ironically the year of Shevchenko's death, a serf was simply chattel, free to be worked as an animal, beaten for any perceived misdemeanour, sold or traded, and in extreme cases, even killed. Shevchenko, as a boy, was witness to all this, including the beating of his grandfather for not showing proper respect for the master. On another occasion, a serf who had been insolent, was conscripted into the army, in those days a twenty-five-year sentence, leaving behind his young wife. It is not surprising that in later life so much of Shevchenko’s poetry is devoted to the recurring themes of peoples' struggles against injustice and a vengeful hatred of those who oppress.

As a youngster, Taras stood out amongst his peers. He was inquisitive and adventurous, often wandering away to search out answers to his many questions. When he was six, he set off to a distant burial mound to see the iron pillars which he imagined held up the sky. Luckily, a villager spotted him on the road and brought him home.

Not long after, the boy was sent to study with a deacon to learn to read and write. He was one of twelve village boys studying, out of some one hundred of that age. This indicates that Taras was exceptional amongst his peers. He excelled at his studies and was sometimes sent to read psalms for the dead, on behalf of the deacon. By this stage, young Taras was already sketching and wanted to become an artist. He would often copy liturgical materials and illustrate the margins of his pages.

Shortly following his mother’s death, when Taras was nine, his father remarried. Life proved to be unbearable with his new stepmother. She had brought three children with her and favoured her own over the Shevchenko children. When Taras was eleven, his father also died.

Shevchenko later summed up his childhood and his feelings in the following words:

I don't describe that little cottage

Beside the pond, beyond the village,

A paradise right here on earth.

That's where my mother gave me birth,

And singing, as her child she nursed,

She passed her pain to me. T'was there,

In that wee house, that heaven fair,

That I saw hell... There people slave

from morn till night... There to her grave

My gentle mother, young in years,

Was sent by want and toil and cares.

There father, weeping with his brood

(And we were tiny, tattered tots),

Could not withstand his evil lot

And died at work in servitude.

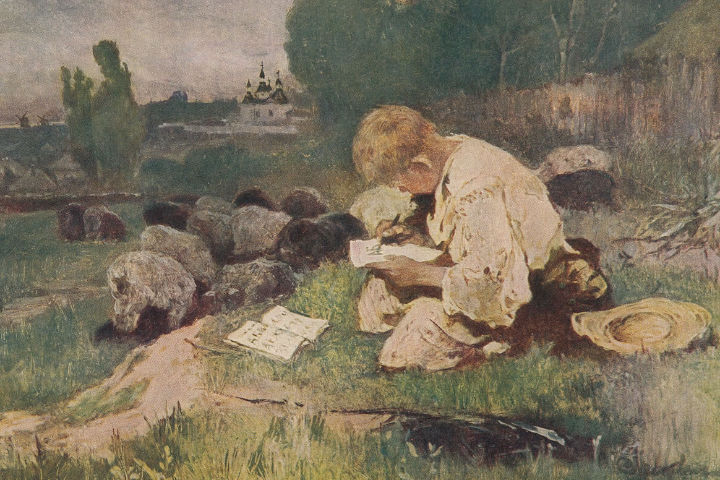

Not long after his father’s death, Taras, fleeing the now intolerable home life as well as the constant abuse and beatings by the deacon, ran away to a second one who painted and allowed the boy to mix colours. Before he left, however, Taras administered a whipping to his drunken abuser. Experiencing similar treatment from his second teacher, Taras ran away again, to a third deacon who painted, but who, after examining the boy's hands, declared him unfit to be an artist. Around the age of thirteen, Taras returned home, where he spent some time as a shepherd and sketched while he worked.

At the age when he was expected to enter formal servitude, Taras came to the attention of Paul Engelhardt who had just inherited the estates of his late father. The boy had finally found a deacon who agreed to teach him to be an artist, but he had to obtain written permission from his master. Paul Engelhardt, not about to lose a servant, refused permission and Taras was assigned to be his kozachok, or houseboy, performing various menial chores.

At this stage in his life, realizing that he could not pursue his dream openly, he began stealing prints and, with a stolen pencil, made copies of them clandestinely.

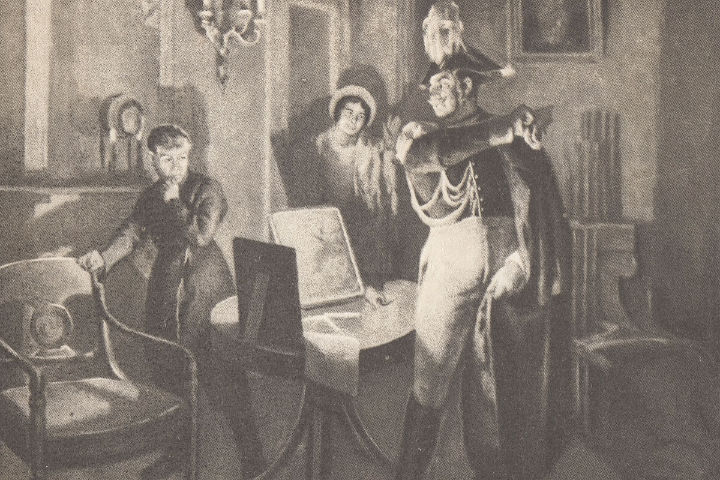

One evening (December 6, 1829, according to Shevchenko’s autobiography), the master and his wife went out to a ball. In their absence, Taras set out his materials and began sketching by candlelight. He was so engrossed that he didn't hear the Engelhardts return. According to Shevchenko, the master savagely pulled him by the ears and slapped his face on the pretext that not only the house, but the whole city could have burned down. The next day the master ordered the coachman Sidorko to give him a good whipping.

Despite this incident, which remained with him for life, Shevchenko continued to draw surreptitiously. Finally, Paul Engelhardt relented and agreed to allow Taras to study with a professional artist, Jan Rustem, at Vilnius University. It seemed that fate had finally smiled on the talented peasant boy. A new world was opening for him, but it was a world of further hardship and distress.

When I Was Thirteen

By Taras ShevchenkoMy thirteenth birthday soon would come.

I herded lambkins on the lea.

Was it the magic of the sun,

Or what was it affected me?

I felt with joy all overcome

As though in heaven...

The time for lunch had long passed by,

And still among the weeds I lay

And prayed to God... I know not why

It was so pleasant then to pray

For me, an orphan peasant boy,

Or why such bliss so filled me there?

The sky seemed bright, the village fair,

The very lambs seemed to rejoice!

The sun's rays warmed but did not sear!

But not for long

the sun stayed kind,

Not long in bliss I prayed...

It turned into a ball of fire

And set the world ablaze.

As though just wakened up, I gaze:

The hamlet's drab and poor,

And God's blue heavens - even they

Are glorious no more.

I look upon the lambs I tend -

Those lambs are not my own!

I eye the hut wherein I dwell -

I do not have a home!

God gave me nothing, naught at all!...

I bowed my head and wept,

Such bitter tears... And then a lass

Who had been sorting hemp

Not far from there, down by the path,

Heard my lament and came

Across the field to comfort me;

She spoke a soothing phrase

And gently kissed my tear-wet face...

It was as though the sun had smiled,

As though all things on earth were mine,

My own... The orchards, fields and groves...

And, laughing merrily the while,

The master's lambs to drink we drove.

How nauseating!... Yet, when I

Recall those days, my heart is sore

That there my brief life's span the Lord

Did not grant me to live and die.

There, plowing, I'd have passed away,

With ignorance my life-long lot,

I'd not an outcast be today,

I'd not be cursing Man and God!...

Orsk Fortress, 1847

Translation by John Weir